There are people whom we witness from afar, who make an imprint, and whose stories even mark the stages of our own life and growth.

There are people whom we witness from afar, who make an imprint, and whose stories even mark the stages of our own life and growth.

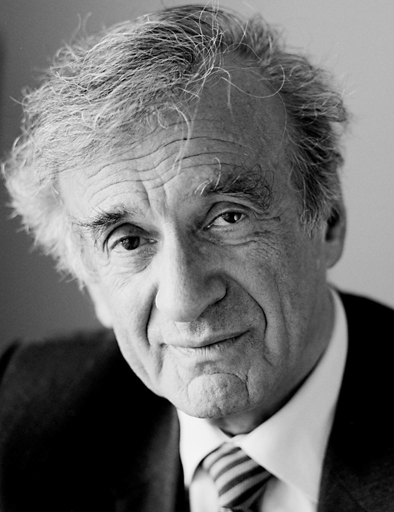

I have a sense that this kind of impact, that defines moments in our lives, for some of us has been discovered through our encounter with the work of Elie Weisel, zichrono livracha, of blessed memory, who died this week. I know this is true for me. I can remember where I was when I encountered the contributions of Elie Weisel, in different points in my own life, and the lessons he taught me as he appeared on my personal timeline.

Do you remember where you were when you first read the book, Night? I was an adolescent and on a family trip. I recall hibernating with the book for hours in the room at the Inn where we stayed. As I read about the horrors of the Shoah—the Holocaust — and the human capacity for cruelty, I remember I became physically ill. For the moment, my optimism was crushed, even as my bond with Elie Weisel, victims and survivors, and the entirely of the Jewish people, grew. From Elie Weisel I learned that what happens to another Jew, and what happens to another person, is connected to me.

Still in adolescence, I remember when President Reagan planned to visit the Bitburg a German cemetery where there are some Nazis buried, and when, just days before while accepting the Congressional Gold Medal from Reagan, Weisel pleaded with him not to visit the cemetery: “That place, Mr. President, is not your place, your place is with the victims of the SS. The issue here is not politics, but good and evil.” Although President Reagan did visit Bitburg, after Weisel’s plea, he added a visit to the Bergen-Belson concentration camp. For years after, my rabbi held up Weisel’s words as a reminder of the importance of religious independence from government, religious voice in the public square, and as the ultimate example of what it means to speak truth to power. From Elie Weisel I learned that when justice is in jeopardy, we speak out.

I cannot remember a time when I did not know about the Holocaust. My childhood religious school principal, was a survivor, and Holocaust education permeated our studies. When I was in elementary school, Elie Weisel visited our religious school. We all knew something important was happening.

When the rabbi came to help us prepare appropriate questions for the Q and A, he listened to our ideas for inquiry about the concentration camps, and then explained that there was something missing. “Someone needs to ask,” he taught, “someone needs to ask”: “What can we do? What should be our take-away?” Sure enough, when it was time for Elie Weisel to visit the classroom, a student asked, “What can we do? What should be our takeaway?” As he responded with lessons of tolerance, justice and humanity, it was clear, this was his favorite question. As important as it was to teach us the history, for Weisel, to bear witness meant to look forward– to look forward to what it would mean to build a better world. From Elie Weisel I learned that we are responsible for tikkun olam, repair of the world.

Even out of the ashes of the Holocaust, that hopeful, future-facing message was Elie Weisel’s enduring contribution. Weisel never let the world off the hook and was a powerful voice against injustice, from Auschwitz to Darfur to Rwanda. And this week, I will add, Louisiana, Minnesota and Dallas. Still, even when he wondered, Will the World Ever Learn, and even when while fighting indifference he doubted the evolution of the human species, Weisel believed in the capacity of every individual to change. He believed everything is possible.

Elie Weisel’s ultimate message of possibility is spoken through his words “And Yet.” He has written: “And Yet–This is the key expression in my work.” The phrase gives us permission to try, even when something feels impossible. Describing his role in recording his memory of the Shoah–the Holocaust, Weisel wrote: “I say we cannot, but we must. I don’t feel we really can use words because there are no words. And yet. My favorite expression is ‘and yet.’ We cannot – and yet. There is no response – and yet I must find one. The attempt should be made.” For Weisel there is no retreat from the effort.

He taught of an enduring hope, writing: “I belong to a generation that has often felt abandoned by God and betrayed by mankind. And yet, I believe that we must not give up on either. … We must choose between the violence of adults and the smiles of children…. Between the ugliness of hate and the will to oppose it. Between inflicting suffering and humiliation on our fellow man and offering him the solidarity and hope he deserves. Or not. I know—I speak from experience—that even in darkness it is possible to create light and encourage compassion. … There it is. I still believe in man in spite of man.”

Perhaps, this call to possibility, “And Yet,” will illumine something of a path of hope for us this week, as our nation encounters institutional racism, anti-police hatred, gun violence and fear.

For somehow, incredibly, after surviving the death camps, Elie Weisel lived with a sense of hope. Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks clarifies the meaning of hope when he distinguishes it from the meaning of optimism. He teaches: “Optimism is the belief that things will get better. Hope is the belief that, if we work hard enough, we can make things better.”

Elie Weisel brought hope into the world. Devoted to the hard work, the vulnerable exposure, and the constant return to painful memory, he believed we can make things better. From the specific tragedy of our people, Weisel taught the danger of all indifference and the path to peace-making and love. From Elie Weisel, I learned lessons of hope for the Jewish People and love for all people.

Weisel’s most cherished title was, “witness”. He believed that when someone listened to a witness, she became a witness. His favorite question was: “What should be our take-away?”

So the lessons I have learned from him in my life –– that what happens to another Jew, & what happens to another person, is connected to me, that when justice is in jeopardy, we speak out, that we are responsible for tikkun olam, repair of the world, and that our witnessing is for the purpose of hope for the Jewish People & love for all people–the lessons I have learned from him in my life, and you in yours, make us witnesses, responsible for the take-away, for his lessons, for his legacy.

May Elie Weisel’s witness and wisdom continue to mark the chapters of our own lives.

May his lessons of love permeate humanity.

And may Elie Weisel’s message of hope inspire us to understand, that even in darkness it is possible to create light.